If it ain't broke... break it.

Why am I “oxidizing” Terraform?

I always had a love-hate relationship with Terraform. I used it a lot in the past and I have some opinions (of course I do), but this blog is not about that.

This blog is about some internals of Terraform, more specifically about Terraform Providers.

So, what are providers?

Let’s say you want to automate the creation of an AWS S3 bucket. You create a bucket.tf file, open it in your editor and create your aws_s3_bucket resource. You then run terraform apply, check the generated plan, and confirm it. If everything works, you will see your shiny brand-new S3 bucket in your AWS console.

How did this happen? How does Terraform know to create resources in AWS? The answer is simple: it doesn’t know, but the AWS Provider does. Terraform just parses the configuration and keeps the state of your stack, then it uses providers for each resource to compute the differences and apply them. Simply put, providers are responsible for translating state changes into the proper API calls that configure the infrastructure to reflect the updates.

I know what you’re thinking: “That’s cool, but I already knew that and I also expected something a bit more technical”. I agree. We need to go deeper.

So, what are providers?

I think the closest analog we can make is plugins. Providers are highly specialized plugins for Terraform. The CLI parses the configuration files and then it finds, loads, and configures the providers used. Those can then be used to plan and apply infrastructure changes.

You can even write your own providers in Go with the Provider/Plugin framework for Terraform. This blog from Hashicorp goes through the process. You define the schemas for your resources and handlers for creating, updating, and deleting them. I tried writing one following the guide and it went pretty smoothly. It was quite an enjoyable and simple process.

“Case closed. That’s it. I can move on with my life.” I thought as I prepared to go home for the day. Little did I know back then, but the ADHD in my brain had other plans.

Not even a few hours later, at home, sitting on the couch, enjoying a good episode of Better Call Saul, a question popped into my head.

Me: So, what are providers?

Also me: What do you mean? We already talked about this. Providers are plugins for Terraform that manage resou…

Me: No. That’s what they do. What are providers?

Also me: You’re terrible.

He’s awful, but he is also right. What are providers? Terraform is written in Go, and providers are also written in Go, so are they dynamic libraries? No. That can’t be. They have a main function. They have to be standalone processes. If that’s the case, how does it get data to/from Terraform? Are they sharing memory, using a socket, or talking via stdin/out? Is this even safe?

So many questions, so few answ… Oh, Hashicorp wrote about this in their docs. How Terraform works with plugins. Seems reasonable, let’s see.

Got it! They are standalone processes! And, even more, they are tiny gRPC servers! From what I understand, Terraform recommends Go and using their framework, but they don’t enforce it. The protocol is documented here, and it looks to me like it could be implemented in any language. You know what this means lads and gals, I’m making a Terraform Provider in Rust.

Ubicloud

If I’m making a provider, I need an infrastructure tool/service to automate. My choice here is ubicloud's hosted offering. They offer very affordable compute, but are still an early-stage startup and don’t have many managed services. Perfect for automation.

By the end of this journey, I want to run a single command and have a fully working multi-node Kubernetes Cluster on top of Ubicloud VMs.

Hello! Future me here. Let me break the fourth wall a bit, and just for full transparency, acknowledge that Ubicloud did reach out to me, but they are not sponsoring this blog. They did, however, credit my account for the amount I spent on their cloud, and they helped out a lot with their API. Many thanks to the team behind Ubicloud! You guys have an awesome product. Now, back to the blog!

Bootstrapping and handshake

As I said above, our provider will have to spin up a gRPC server, and we’ll get to the implementation of that soon, I promise, but before that, we have to tell Terraform how to connect to this server.

I have found this very up-to-date guide from 7 years ago (lucky me). It gave me some insight into how to do this step, but it was so outdated, that I had to look at the code myself. So, here’s how it works:

- When Terraform starts up our process it gives us a few basic details in the form of environment variables. This includes a range for the port we should use, but also a client certificate for mTLS.

- Then it waits for a message from our

stdoutin the following format:CORE-PROTOCOL-VERSION | APP-PROTOCOL-VERSION | NETWORK-TYPE | NETWORK-ADDR | PROTOCOL | SERVER-CERT. This message will look something like this:1|1|tcp|127.0.0.1:1234|grpc|{base64-encoded-pem}. - After it parses the message, it attempts to connect to the server with the details provided.

- Everything else happens over gRPC.

Looks simple enough. First, we have to generate a server certificate to use for mTLS, then we need to spin up a gRPC server and listen on a port in the range provided by Terraform (I just hard-coded it), use the generated server certificate, and also trust the client certificate received from Terraform. When this is ready, we can print the properly formatted message on stdout.

You can find some of the code for these steps here, but mostly here. I used tonic for the server and rustls for the TLS stuff (it got much easier to do this sort of stuff in Rust than it used to be; kids these days won’t know the struggle).

We can now proceed to the implementation of the gRPC server. After a bit of digging, I’ve found the proto file for the tfplugin protocol v6. Other services do exist, but this is the only one required to make this work. I used the proto file combined with information from the protocol documentation to implement everything.

The schema

Terraform parses and validates configuration before it even thinks about planning or applying changes to the state. To do this it needs a schema for each provider to validate against. This feature is also used in the LSP to provide IntelliSense and other smart editor features while editing configuration.

Given that Terraform doesn’t know anything about resources, only the providers do, I expected an RPC call to get the schema from us. And, sure enough, the first thing we need to implement is the GetProviderSchema RPC.

You can check the implementation of this here. It’s pretty simple. You need to provide a provider schema that specifies the data used to configure the provider (credentials, default region, and other stuff like that), resource, and datasource schemas (for each resource/datasource handled by the provider) but also some provider metadata.

This response can also return some diagnostics (I’m not sure what diagnostics you could give from the GetProviderSchema RPC, as I don’t see how this could fail, but whatever). Actually, all responses can return diagnostics, which I find pretty neat.

Each schema has some basic information (like the name, description, versioning, and deprecation info), but also a list of fields. Each field has, again, basic information (name, description, etc.), and also validation information (the type of the field, if it’s optional, sensitive, computed, etc.). You could also define nested block types, for more complex inputs/outputs, but I didn’t get into that yet.

Now, Terraform will go ahead and validate the configuration using the schema. It will also get your opinion with the ValidateProviderConfig, ValidateResourceConfig, and ValidateDataResourceConfig RPCs.

Configuration

The provider is started, the schema is validated, and now, we can get to work. Or can we? We have one more step before we can get to creating VMs. We need to get our provider configuration from Terraform. For our use case, this includes the Ubibloud username, password, and project ID.

Luckily for us, we don’t have to do anything. Terraform will call the ConfigureProvider RPC with the configuration data.

The format rant

In what format do you think Terraform will ship this data to us? JSON? XML? Any reasonable text format? Any reasonable standard binary format?

Good guesses, but the answer is cty. If you're thinking What? What is cty?, I felt the same way. cty is a format based on msgpack but with some gotchas: they add type information in the message (only sometimes), they have a special representation for empty values (painful) and the only implementation I found was in Go (lucky me).

My other question is: why Terraform, why? They already use JSON in some other places in the RPC, they’re not even consistent with their format! On top of the fact that they already use gRPC, if they wanted an efficient binary format, why can’t they just use protobuf for this? It’s already there! Or even just msgpack. Why do they use this magic on top?

Anyway, I found this great crate rmp for parsing msgpack (it even works with serde) and I managed to hack in empty values (but only for strings, and it’s very hacky).

Finally doing some work

We are now ready to do some API calls. I quickly threw together a Ubicloud API client (it’s a very small API at the moment) to manage VMs. You can find it here but I would highly discourage you from using it, as their API is not stable yet (and no docs published).

Let’s start with the plan step. We have to implement the PlanResourceChange RPC (you can find the complete implementation here). We get as inputs the prior state and the configuration we have to apply. The prior state is optional. In that case, it means that the resource is newly added. The config can also be missing. In this case, it means that the resource needs to be deleted. There are many other cases to handle, and most of them we’ll need to reuse in the apply step, so I created a utility function to compute the resource state and the action we need to take, you can find it here.

We can now continue with the apply step. It’s very similar to the plan step, but we need to implement the ApplyResourceChange RPC instead (full implementation here). The inputs are mostly the same but we also get the previously planned state and we can use it to make sure the plan shown to the user is consistent with the actions we are actually taking. We will use that same utility function from before to compute the new resource state and the actions, and then we can perform those actions using the API client.

One important mention here is that we have only one resource type, so I didn’t have to bother to check the resource we are processing. In a real implementation, the configuration, plan, and actions would be completely different between, let's say, a VM and a VPC.

That’s it! We can now automate the creation of Ubicloud VMs!

Automate, automate, automate

Now, for the grand finale, I want to have a fully working Kubernetes cluster, with a domain attached to it, and have it serve traffic from a container, through an ingress, with a real SSL certificate - all 100% automated.

Let’s begin with the infrastructure part of this madness. I have a Terraform configuration here that creates 3 VMs on Ubicloud (one master, 2 workers). To assist that, we also need to generate an SSH key pair for the SSH connection. We also have to create DNS records with the public IPs of the VMs, and for that, I used the Namecheap provider. The public IPs are taken as outputs of the VM resources. I also generated the K8s token with Terraform, as it was convenient. I want to use Ansible for the next step, so I also used the Ansible provider to output the connection information as hosts and variables.

Just a note here, secrets will be stored in plain text in the state, and I strongly recommend using a secret store (like Vault) instead.

Now that we have some VMs, let’s get Kubernetes going. I used Ansible and the Terraform inventory plugin to import the hosts defined in Terraform. For networking, I wanted to use a VPN, and my choice was wireguard. I created this basic playbook that runs on all nodes to update apt and install wireguard. We can now move on to setting up the cluster. Starting with the master node configuration, we prepare the networking stuff and install our K8s distribution of choice: k3s. The same steps are taken for the worker nodes too, with the main difference being that we configure them as workers.

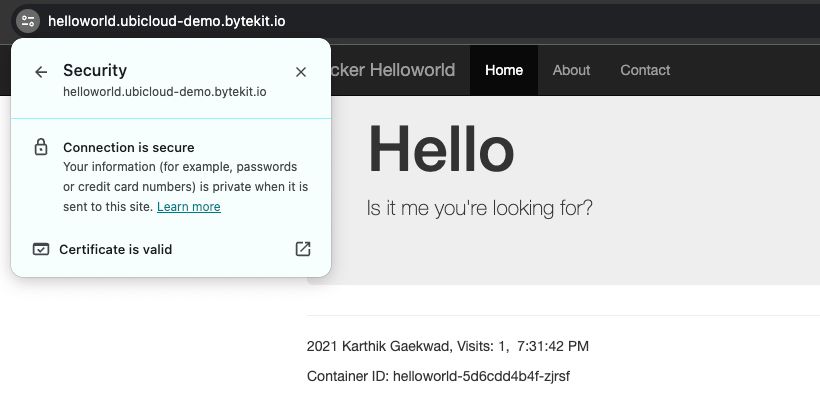

Now we just need to use Helm to install the ingress-nginx and cert-manager charts in the cluster and then we can deploy our basic workload with kubectl. And, we’re done! Let’s take a look at it.

Beautiful! Now we can just terraform destroy it out of existence, and it’s like it never happened!

Conclusions

This was a very interesting journey for me! I love learning about and exploiting the internals of seemingly “magic” systems.

Thanks again to Ubicloud for helping me out during the development of this madness. It’s a really cool platform and they have an awesome team and a lot of fresh ideas! You should check them out, here’s the link again.

These posts take a lot of time to prepare and write. If you like the content I’m making and you wish to support these kinds of useless but fun journeys, I have a GitHub Sponsors page now!

That being said, thanks for walking with me! Have a nice one!