Do you even JIT?

I’m working on a programming language and a toolchain for it. Actually, I’m working towards complete computing independence: my programs, my OS, my language, my compiler, my computer, my CPU, my ISA… you get the point.

On the road to this deep desire of mine, I want to learn as much as possible. One thing that brings me joy every time I think about it is a JIT compiler. I’m fascinated by the idea of allocating executable memory, encoding instructions, writing raw op-codes in that memory, and then jumping to it.

But before I go straight into writing a JIT for a language that doesn’t exist yet, I thought it’s better to write one for a simpler language. I saw some people online writing JITs for Brainf*ck, and I will do the same. It’s such a simple language, parsing will be trivial and we won’t spend any time in the compiler “frontend”, perfect for our use case.

Oh, I almost forgot to mention 🙂 We’ll build this in Rust of course. You can find the code here.

The language

Brainf*ck, the language, has 8 possible operations, each encoded by a single character. A program in Brainf*ck is a sequence of these characters. Any character that doesn’t encode an operation is ignored.

Brainf*ck, the runtime, has some linear memory (some runtimes have infinite memory, but we won’t), an instruction pointer that steps through each operation in the program (except for loops), and a data pointer to one cell in the memory. In the standard implementation, each cell has 1 byte, but some implementations use 4-byte-wide cells (we will also do that) to simplify writing programs.

Here’s what you can do in a Brainf*ck program:

>: Increment the data pointer<: Decrement the data pointer+: Increment the value at the data pointer-: Decrement the value at the data pointer.: Output the value at the data pointer,: Accept exactly one byte of input and store the value at the data pointer[: If the value at the data pointer is zero, instead of moving the instruction pointer forward to the next operation, it jumps to the operation after the matching closing]]: If the value at the data pointer is non-zero, instead of moving the instruction pointer forward to the next operation, it jumps to the instruction after the matching opening[

That’s it. That’s Brainf*ck. You can read other boring stuff about the language online, but this is enough for us to continue.

Parsing

Before we start, I need to warn you that this might be the simplest parser in history. The first thing we must do is to define an enum to represent all the possible operations we might have. It would look something like this:

pub enum Operation {

Right,

Left,

Increment,

Decrement,

Output,

Input,

Loop(Vec<Operation>),

}

Nothing special, except for the Loop operation is represented by a list of contained operations.

Now, let’s get to parsing. What we want to achieve is to convert a string like +>+ to a list of the following operations: Increment, Right, Increment. Here’s how we can do this:

pub fn parse_input(input: &mut Chars<'_>) -> Vec<Operation> {

let mut ops = vec![];

loop {

let Some(c) = input.next() else {

break;

};

match c {

'<' => ops.push(Operation::Left),

'>' => ops.push(Operation::Right),

'+' => ops.push(Operation::Increment),

'-' => ops.push(Operation::Decrement),

'.' => ops.push(Operation::Output),

',' => ops.push(Operation::Input),

'[' => {

let inner = parse_input(input);

ops.push(Operation::Loop(inner));

}

']' => break,

_ => {}

};

}

ops

}

We iterate over each character in the input and we try to match it against every possible encoding of the operations, consuming one at a time. If it doesn’t match, we can ignore it. The only interesting thing here is, again, the loop. We take a mutable reference to a Chars iterator as the input to our “parser”, and the reason for this is the loop. We can simply recursively call parse_input to parse our loop, as the iterator will just continue to consume our original input, and then we store the result as the inner operations of the loop. That means we will be left with a single ] character, and we can just break when we get to it. Amazingly simple!

Now, there’s a problem here. Actually, not a problem, but an easy-to-do optimization that will help us big time later.

At the moment we would convert the string +++ into [Increment, Increment, Increment]. This means that later, we will have to process 3 operations. What if instead, we could parse +++ as [Increment(3)]? This way we would only have to process one operation. This “reduction optimization” also applies to the decrement, left and right operations.

To implement this, first, we need to alter our enum a bit, as we now need to store how many times the operation is repeated:

pub enum Operation {

Right(u32),

Left(u32),

Increment(u32),

Decrement(u32),

Output,

Input,

Loop(Vec<Operation>),

}

Also, in parse_input we must initialize them with a value:

'<' => ops.push(Operation::Left(1)),

'>' => ops.push(Operation::Right(1)),

'+' => ops.push(Operation::Increment(1)),

'-' => ops.push(Operation::Decrement(1)),

Now, let’s write our optimizer:

pub fn optimize_ops(ops: Vec<Operation>) -> Vec<Operation> {

let mut optimized = vec![];

let mut iter = ops.iter().peekable();

loop {

let Some(op) = iter.next() else {

break;

};

match op {

Operation::Right(n) => {

let mut count = *n;

while let Some(Operation::Right(n)) = iter.peek() {

count += n;

iter.next();

}

optimized.push(Operation::Right(count));

}

// other operations

}

}

optimized

}

We take a peekable iterator (that means we can look into the future without cloning). We can then look at every operation, and if it’s one that we can optimize, we can count how many consecutive operations of the same kind we have. We then store a single operation with the matching kind and count.

That’s it. That was the parser. The full implementation is here. We could implement a better, single-pass parser, but this will do just fine.

A caveman’s JIT

The first challenge is done. We have the operations that we need to JIT. Now we need to learn to JIT. But before we can learn to JIT, what is JIT? Did I say JIT too many times? JIT JIT JIT JIT.

So, what does it mean to JIT compile some code? Well, it means that we have a program that takes some input, compiles it to machine code, allocates some memory, marks it as executable, stores the machine code in that memory, and then redirects the execution to it. Isn’t it amazing?

Don’t panic! Take a deep breath, and let’s take it one step at a time. First, let’s use libc to allocate some executable memory that we can write to.

const PAGE_SIZE: usize = 4096;

// ....

let size = page_count * PAGE_SIZE;

let page: *mut u8 = unsafe {

#[allow(invalid_value)]

let mut page: *mut libc::c_void = std::mem::MaybeUninit::uninit().assume_init();

libc::posix_memalign(&mut page, PAGE_SIZE, size);

libc::mprotect(

page,

size,

libc::PROT_EXEC | libc::PROT_READ | libc::PROT_WRITE,

);

libc::memset(page, 0xc3, size); // fil with ret

page as *mut u8

};

What’s the deal with MaybeUninit? Well, Rust doesn’t like uninitialized variables, but libc likes to store return values in arguments… so, we need a pointer to somewhere in memory that is safe for libc to store the result in. This is why we have the page variable and we pass it to memalign as a mutable reference. We have a mutable variable that will store in the future a mutable pointer to some memory. Yeah… I never said this was easy.

Some platforms have some limitations around the alignment of executable code, we can use memalign to ensure that we have properly aligned memory. We can also use it directly to allocate the memory we need. Then, we can simply use mprotect to make it readable, writeable, and, most importantly, executable. We can also fill it with 0xc3, the op-code for the ret instruction on x86_64 (we will later cast this pointer as a function, so if something goes wrong and we don’t properly emit a ret at the end, we can at least be sure the function will exit).

Now, let’s write some machine code in that memory and try to execute it. In the x86_64 calling convention, the return value is stored in the rax register. So, to begin, let’s store an arbitrary value (69) in rax and then return.

unsafe {

page.offset(0).write(0x48); // mov rax, 0x45 (69)

page.offset(1).write(0xc7);

page.offset(2).write(0xc0);

page.offset(3).write(0x45);

page.offset(4).write(0x00);

page.offset(5).write(0x00);

page.offset(6).write(0x00);

page.offset(7).write(0xc3); // ret

};

If you don’t know how to encode x86_64 instructions in your head (unlike me, duh), that’s fine, there is a trick you can use. Open up an editor, write some assembly, and compile it, then use objdump -d on the resulting object file to decompile it (it will show you each instruction and how it’s encoded). You can find a setup for this in the repo (of course I never used it, duh).

We can proceed to run the machine code we just wrote. We just have to completely safely™ transmute it to a function type and call it.

let run: fn() -> i32 = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(page) };

let result = run();

dbg!(result); // outputs: [src/main.rs:78] result = 69

If everything went fine, and you didn’t SIGSEGV yet, you should see your output now. To see if you understood this, try to change the machine code to output another completely arbitrary value, let’s say 42.

Send it.

Are you still here? Did you do it? Awesome! Oh, you have some questions? Ok, let’s hear it.

You: What happens on architectures other than x86_64?

Me: #[cfg(not(target_arch = "x86_64"))] panic!("JIT is only supported on x86_64 CPUs");

Also me: Anything else?

You: Umm… Will we have to encode every instruction the “caveman” way?

Me: Great question!

We can use the amazing crate called iced_x86. It’s an amazing x86_64 encoder, especially with the CodeAssembler feature. It allows us to convert our caveman machine code to this:

let mut code = CodeAssembler::new(64)?;

code.mov(asm::rax, 69_i64)?;

code.ret()?;

let bytes = code.assemble(page as u64)?;

for (i, byte) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

unsafe {

page.offset(i as isize).write(*byte);

}

}

How cool is that? We also need some memory to work with. We can do that on the Rust side. We can allocate an i32 slice and modify the signature of the transmuted function to accept a mutable pointer to it as the first argument:

let run: fn(*mut i32) = unsafe { std::mem::transmute(page) };

let mut memory = vec![0i32; 5_000];

let result = run(memory.as_mut_ptr());

dbg!(result);

Let’s start generating some real machine code to match our Brainf*ck program. We need to choose a register to store our pointer. I went with rsi, I’ll show you later why.

pub fn emit(ops: Vec<Operation>, code: &mut asm::CodeAssembler) -> Result<()> {

#[cfg(not(target_arch = "x86_64"))]

panic!("JIT is only supported on x86_64 CPUs");

code.mov(REG_MEMORY, asm::rdi)?;

emit_operations(ops, code)?;

code.ret()?;

Ok(())

}

fn emit_operations(ops: Vec<Operation>, code: &mut asm::CodeAssembler) -> Result<()> {

for op in ops.iter() {

match op {

//.....

}

}

Ok(())

}

We start by emitting a mov REG_MEMORY, rdi. Why? Because the x86_64 calling convention is to store the first argument in rdi and we need that value (the pointer to the memory) in our memory register. We then emit the operations (we will get to it in a bit), followed by ret.

First, let’s do the basic operations:

// ....

Operation::Left(n) => {

code.sub(REG_MEMORY, (n * 4) as i32)?;

}

Operation::Right(n) => {

code.add(REG_MEMORY, (n * 4) as i32)?;

}

// ....

For the left and right operations, we just need to move the data pointer forward/backward some elements. In our case, each element takes up exactly 4 bytes, and we need to move N elements, so we just add or sub (n * 4) to our memory register.

The story for increment and decrement is mostly the same:

// ....

Operation::Increment(n) => {

code.add(asm::dword_ptr(REG_MEMORY), *n)?;

}

Operation::Decrement(n) => {

code.sub(asm::dword_ptr(REG_MEMORY), *n)?;

}

// ....

We do need, however, to take the dword_ptr to our memory register (aka, the value at that pointer, not the pointer itself), but other than that, it’s the same thing.

Output and input are a bit more interesting:

Operation::Output => {

#[cfg(target_os = "macos")]

code.mov(asm::rax, 0x2000004_u64)?; // syscall number

#[cfg(target_os = "linux")]

code.mov(asm::rax, 0x1_u64)?; // syscall number

code.mov(asm::rdi, 1_u64)?; // file descriptor

code.mov(asm::rsi, REG_MEMORY)?; // buffer

code.mov(asm::rdx, 1_u64)?; // length

code.syscall()?;

}

Operation::Input => {

#[cfg(target_os = "macos")]

code.mov(asm::rax, 0x2000003_u64)?; // syscall number

#[cfg(target_os = "linux")]

code.mov(asm::rax, 0x0_u64)?; // syscall number

code.mov(asm::rdi, 0_u64)?; // file descriptor

code.mov(asm::rsi, REG_MEMORY)?; // buffer

code.mov(asm::rdx, 1_u64)?; // length

code.syscall()?;

}

For output and input, we need to make some syscalls. MacOS 64-bits and Linux are quite similar (other than the syscall number, they are identical), but other operating systems are different and I don’t plan to support it. The output is mapped to a write syscall to STDOUT from the current memory location with the length one. The input is mapped to a read syscall from STDIN to the current memory location with the length one.

And, here’s the reason I chose rsi as my memory register. For these syscalls, we need to pass the buffer as the second argument. Conforming to the calling convention for syscalls the second argument must go in rsi , this means that we are redundantly encoding mov rsi, rsi , so we can remove it! We saved one instruction for each output/input operation!

This also reminded me I need to do something quickly:

#[cfg(not(any(target_os = "macos", target_os = "linux")))]

#[cfg(not(target_arch = "x86_64"))]

#[cfg(not(target_pointer_width = "64"))]

panic!("JIT is only supported on x86_64 Linux and macOS.");

Good! The last step is emitting the code for loops:

// ....

Operation::Loop(inner_ops) => {

let mut start = code.create_label();

let mut end = code.create_label();

code.cmp(asm::dword_ptr(REG_MEMORY), 0)?;

code.je(end)?;

code.set_label(&mut start)?;

emit_operations(inner_ops.clone(), code)?;

code.cmp(asm::dword_ptr(REG_MEMORY), 0)?;

code.jne(start)?;

code.set_label(&mut end)?;

}

// ....

We have to create two labels: one for the start of the loop and one for the end. The first step is to emit the check if the value at the current memory address is zero, and if it is, we jump to the end. Next, we can set the location of the start label and emit the inner operations of the loop, followed by checking if the value at the current memory address is non-zero, and if it is, we jump to the start. The last step is to set the label for the end.

Conclusions

That was it. We just wrote a JIT compiler, including the parser and the emitter. You can find the complete code here, along with some examples and some other optimizations.

Is this useful tho? No, just fun.

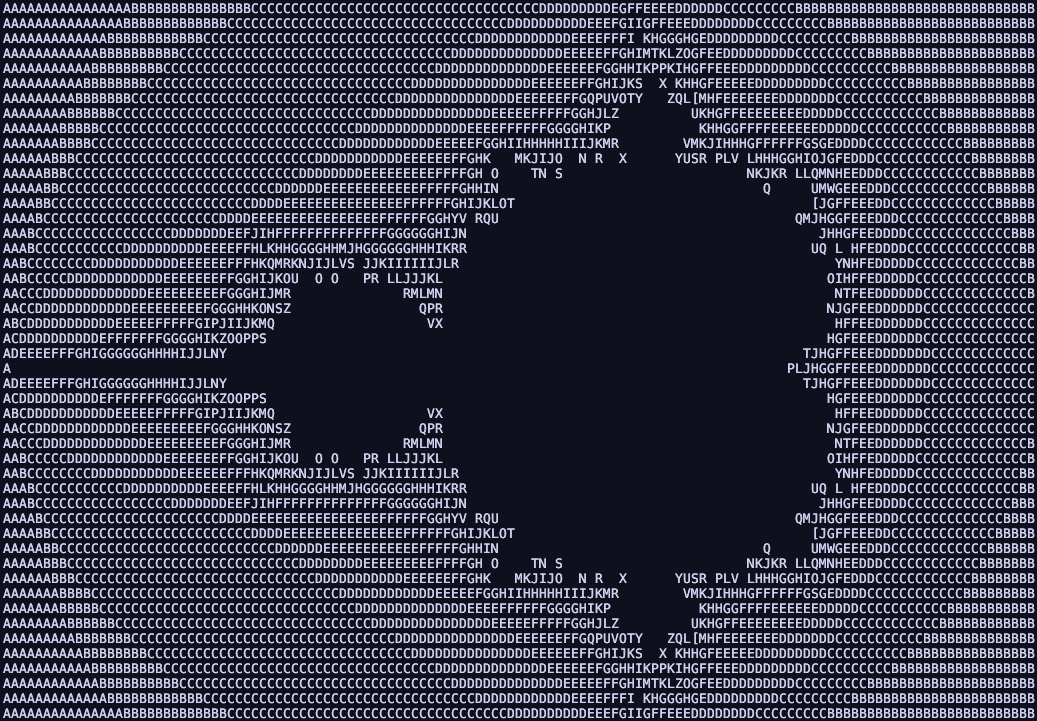

Like, how fast does Brainf*ck have to be anyway? Is not like someone is crazy enough to write something like a Mandelbrot Set view in Brainf*ck, right? (uhm).

These posts take a lot of time to prepare and write. If you like the content I’m making and you wish to support these kinds of useless but fun journeys, I have a GitHub Sponsors page now!

That being said, thanks for walking with me! Have a nice one!

Oh, and also, before I go, here's a photo of a Mandelbrot Set view someone wrote in Brainf*ck (running on this JIT).